BATTLE OF PANJAWAI AND BEYOND

Hey everybody! First off I apologize for the length of this email, as it contains two weeks worth of Afghanistan fun. I am doing well and brutally honest I have enjoyed this last couple of weeks. Seven years of training culminating in 14 action packed days. At first I wasn’t going to write a lot of detail about what happened, because some people might find it upsetting. However, when I got back to Kandahar Air Field (KAF) and read the deplorable media coverage that the largest operation Canadians have been involved in since Korea, I really felt I had to write it all down, to give you all (and hopefully everyone you talk to back in Canada) an appreciation for what we are really doing here in this “state of armed conflict” (lawyers say we can’t use the word “war”, I don’t know what the difference is except for it being far more politically correct.)

On the night of the 7th around 2200 hrs local C Company Group (with yours truly attached as their FOO) rolled for Pashmul. As we arrived closer to the objective area we saw the women and children pouring out of the town… not a good sign. We pushed on and about 3 km from our intended Line of Departure to start the operation we were ambushed by Taliban fighters. At around 0030hrs I had my head out of the turret crew commanding my LAV with my night vision monocular on. Two RPG rounds thundered into the ground about 75m from my LAV. For about half a second I stared at them and thought, “huh, so that’s what an RPG looks like.” The sound of AK 7.62mm fire cracking all around the convoy snapped me back to reality and I quickly got down in the turret and we immediately began scanning for the enemy. They were on both sides of us adding to the “fog of war”. We eventually figured out where all of our friendlies were, and where to begin engaging. We let off about 20 rounds of Frangible 25mm from our cannon at guys about a 100m away before we got a major jam in our link ejection chute. We went to our 7.62 coax machine gun, and fired one round before it too jammed!! Boy was I pissed off. I went to jump up on the pintol mounted machine gun, but as I stuck my head out of the LAV I realized the bad guys were still shooting at us and that the Canadian Engineers were firing High Explosive Incendiary 25mm rounds from their cannon right over our front deck. I quickly popped back down realizing that was probably one of the stupider ideas I have ever had in my life J Eventually after much cursing and beating the crap out of the link ejection chute with any blunt instrument we could find in the turret, we were back in the game. The first Troops in Contact (TIC) lasted about two hours. The radio nets were busier than I had ever heard before and we realized that A and B Coys. as well as Reconnaissance Platoon had all been hit simultaneously, showing a degree of coordination not seen before in Afghanistan. The feeling amongst the Company was that was probably it, as the enemy usually just conducted hit and run attacks. Boy, were we wrong! We continued to roll towards our Line of Departure and not five minutes later as we rolled around a corner, I saw B Coy. on our left flank get hit with a volley of about 20 RPGs all bursting in the air over the LAVs. It was an unreal scene to describe. There was no doubt now that we were in a big fight.

We pushed into the town following the Company Commander behind the lead Platoon. This was not LAV friendly country. The entire area was covered in Grape fields, which due to the way they grow them are not passable to LAVs, and acres of Marijuana fields which due to irrigation caused the LAVs to get stuck. The streets were lined with mud compounds and mud walls just barely wide enough to get our cars through. After traveling about 300m our lead platoon came under attack from a grape drying hut in the middle of what can only be described as an urban built up area. The Company Commander then issued a quick set of frag orders and I was about to participate in my first ever Company attack. He signaled for me to dismount and follow him. It was an uncomfortable feeling dismounting from the turret, as the only way out is through the top of the turret. I was standing probably 15 feet high in the air with friendly and hostile rounds snapping and cracking in the air everywhere. Needless to say I got down quick. I went to the back of my LAV and banged on the door to signal we were dismounting. As the Master Bombardier opened the door he went pale as we were only 20m from where they had previously been ambushed and where Nich had died. Regardless, we soldiered on. We grabbed our radios and followed the Company Commander. We went into a compound that was actually the same one Howie Nelson had dropped a 1,000lb bomb on after the attack in May. We went up to a second story ledge on a mud wall, and the Company Commander pointed out a compound and said “can you hit that?” I lased the building and found out it was only 89m away. Back in Canada we never bring Artillery in much closer than a 1000m, so you can imagine what I was thinking. I sat down and did the math (those of you who know my mathematical skills are probably cringing right now!). I looked at him and said that in theory and mathematically we would be okay where we were, but I made him move one of the other Platoons back 150m. A funny story as I was doing the math, an American ETT Captain working with the ANA looked down at me and said “There are no ANA forward of us” I responded “Roger”, to which he said “good” fired three rounds and said “Got him”. I then realized that he had asked me a question and had not stated a fact (for some reason everyone seems to think that the FOO magically knows where all the friendlies are). Through all the gunfire I had missed the infliction in his voice. I looked at him and said, “Hey, I have no idea where your ANA are, you’re supposed to look after them!” Luckily it wasn’t a friendly he had shot at.

We started the Fire Mission with the first round landing about 350m from my position. The noise of Artillery whistling that close and exploding was almost deafening, the FOO course sure hadn’t prepared me for this! Master Bombardier and I debated the correction for a second and eventually agreed upon a Drop 200m, mostly because we needed to get rounds on that compound ASAP as we were taking heavy fire. The round came in and landed a bit left of the compound. We lased the impact and found out it was 105m from us. We gave a small correction and went into Fire For Effect with 50% Ground Burst and 50% Air Burst. The rounds came in 85m from us, right on the compound. Truly I did not appreciate the sheer frightening and awe-inspiring nature of proximity (the air burst rounds). I then had the worst moment of my military career as one of the Sections began shouting “Check Fire, Check Fire!” on the net, followed quickly by their Platoon Commander saying they had casualties and to prepare for a 9 Line (air medical evacuation request). It turned out the two events were unrelated but for a while I thought I had injured or even worse killed a Canadian. In actuality the Section that called Check Firing was actually the furthest of anyone in the Company from the shells and had panicked (which led to a lot of ribbing and jokes from their buddies afterwards who had all been closer). The 9 Line was for an ANA soldier who had been struck 5 minutes before. However unfortunate, I was definitely relieved to here all that.

Day one carried on with several more small skirmishes and me moving from compound to compound to set up Observation Posts (OPs), from which I could support the Company’s movement. I never thought that in my career I would literally be kicking in doors and leading a three man stack, clearing room after room to get to my OPs.

|

We ended the day, which had seen us in contact for 12 straight hours, by sleeping beside our vehicle in full battle rattle for about an hour with sand fleas biting us. They are the single most ignorant and annoying bug ever. The next morning started off with what seemed like a benign task. We were to clear the grape fields to the south of our objective area. Intelligence said there was nobody there and this would only take us a couple of hours. About an hour into the clearing operation we came under contact from a heavily fortified compound. Unfortunately we had a young fellow killed early in the engagement when the infantry tried to storm the compound. They met fierce resistance, far greater than expected. (I didn’t know the young soldier personally, but do recall thinking how fearless he was a week earlier when I saw him running around the Brit compound with a Portuguese flag right after England had lost in the World Cup. I was impressed by his peers and friends and how professionally they carried on after his death.) After the attempted storming of the compound, the Company Commander came to me and said “right, we tried that the old fashioned way, now I want you to level that compound.” As I was coming up with a plan for how I would do this, we had a call sign I had never heard before check in. It was Mobway 51. Ends up he was a Predator Unmanned Aerial Vehicle armed with a hellfire missile. I don’t know how he knew we needed help or what frequency we were using, and frankly I don’t care, he was a blessing. When the Company Commander asked me what the safety distance for a hellfire was I literally had to go to the reference manual I carry (J Fires Manual) because I had never seen one before and had no idea what it actually could do. I told him the safety distance was 100m. To which he asked how far we were from the compound – the laser said 82m. We debated the ballistic strength of the mud wall beside us and in the end he decided to risk it. Nothing like seeing an entire Company in the fetal position pressed up against a mud wall! The hellfire came in and it was the loudest thing I have ever heard. Three distinct noises: the missile firing, it coming over our heads and the boom. For about 30 seconds we couldn’t see anything but a cloud of dust.

Then when the dust settled the Platoons started hooting and hollering. The compound barely even looked the same. (At this point our embedded journalist Christie Blanchford from the Globe and Mail had enough and left us, can’t blame her I guess.) The Company again tried to clear the compound but still met resistance. So we lobbed in 18 artillery shells 82m from us (even closer than the day before) and then brought in two Apache Attack Helicopters. On the second rocket attack (I actually have video of this) the pilot hit the target with his first rocket and the second one went long and landed just on the other side of the mud wall from us. It engulfed us in rocket exhaust, but thankfully no one was hurt. When the hellfire had gone off it had started a small building in the compound on fire and suddenly we started getting secondary explosions off of a weapons cache that was in it. Everything started exploding around us, and the two guys that had not listened to me to press up against the wall got hit with shrapnel, both in the legs. One was the Company Commander’s Signaler, a crazy Newf, who was cracking jokes even with shrapnel in his leg. The medic dealt with him and I went over to the American ETT Captain who was only a few feet from me and began doing first aid on him. He looked liked he was going into shock, until his American Sergeant came up behind me and said “Shit Sir, that’s barely worth wearing a Purple Heart for!” I was surprised how much first aid I actually remembered, and the only difficult part was trying to cut off his pant leg because American combats are designed not to tear, making them particularly difficult to cut! In the end we took the compound and captured a high level Taliban leader who was found by the infantry hiding in a sewage culvert, begging for the shelling to stop. As well, we found a major weapons cache, which the engineers took great delight in blowing up. Unfortunately the assault had cost us one killed, two wounded, a Section commander had blown his knee throwing a grenade and four guys had gone down to extreme heat exhaustion. We found out though that this was a Taliban and Al Qaeda hot bed and that they had been reinforced by Chechen and Tajik fighters (which I guess means we really got a chance to take on Al Qaeda and not just the Taliban).

Day three was uneventful for C Coy. and we prepared to go back to our FOB. Which would have been good because I had come down with a cold… not what I needed in combat (umm, I mean state of armed conflict!) Unfortunately that was not to be. A British Company from 3 Para had been isolated and surrounded by Taliban in the Helmand Province in the Sangin District Center. They were running out of food and were down to boiling river water. They had tried to air drop supplies but they ended up landing in a Taliban stronghold (thank you air force). C Coy. was tasked to conduct an immediate emergency resupply with our LAVs. We headed off to what can only be described as the Wild West. The Company (B Coy) of the Paras that was holding the District Center had lost four soldiers there and was being attacked 3 to 5 times a day. We rolled in there after a long and painful road move across the desert. When we arrived in Sangin the locals began throwing rocks and anything they could at us, this was not a friendly place. We pushed into the District Center, and during the last few hundred meters we began receiving mortar fire.

They never taught me on my LAV Crew Commander course how to command a vehicle with all the hatches closed using periscopes in an urban environment. I truly did it by sense of touch, meaning as we hit the wall to the left I would tell the driver to turn a little right!! We resupplied the Brits and unfortunately it turned dark and we couldn’t get out of there, so we had to spend the night. We were attacked with small arms RPGs and mortars three times that night, I still can’t believe that the Brits have spent over a month living there under those conditions. They are a proud unit and they were grateful but embarrassed that we had to come save the day. And as good Canadians we didn’t let them hear the end of being rescued by a bunch of colonials!!

We left Sangin again thinking we were headed home. We made it about 40km before we were called back to reinforce the District Center and help secure a helicopter landing site. As we sat there we received orders that we were now cut to the control of 3 Para for their upcoming operation north of Sangin. This was turning out to be the longest three day operation ever!!! Enroute we were engaged by an 82mm mortar from across a valley. I engaged them with our artillery, it felt a lot more like shooting in Shilo as they were 2.8km away as opposed to the 100m or less my previous engagements had been. We went round for round with them in what Rob, the Troop Commander firing the guns for us, called an indirect fire duel. In the end he said the score was Andrew 1 Taliban O and there is no worry of that mortar ever firing again. We rode all through the night (with my LAV on a flat tire) and arrived right as the Paras Air Assaulted onto the objective with Chinook helicopters. There were helicopters everywhere. It was a hot landing zone and they took intense fire until we arrived with LAVs, and the enemy ran away. It was a different operation as we were used to a lot more intimate support tanks to shoot the Paras in. It was impressive to watch them though, they are unbelievable soldiers.

We left the operation about 25 hours later (still3 going on no sleep) and thought that for sure we were now done this “three day op”. But as we were withdrawing to secure the landing zone for the Brits (under fire from 107mm rockets and 82mm mortars) we received Frag orders to conduct a sensitive sight exploitation where the Division had just dropped two 1000lbs bombs. Good old C Coy. leading the charge again!

We drove to the sight and saw nothing but women and children fleeing the town. I thought, “here we go again.” Luckily this time I found a good position for observation with my LAV and did not have to go in on the attack. The Company quickly came under attack from what was later estimated as 100+ fighters. For about 15 minutes we lost communications with the Company Commander and a whole Section of infantry as they were basically overrun. The Section had last been seen going into a ditch that was subsequently hit with a volley of about 15 RPGs; I thought we had lost them all. I had Brit Apaches check in and they did an absolutely brilliant job at repelling the enemy. The only problem was I couldn’t understand a word the pilot was saying because of his accent! Luckily I had the Brit Liaison Officer riding in the back of my LAV. I ended up using him (a Major) as a very highly paid interpreter to help me out. After about an hour long fight the Company broke contact (but lived up to the nickname the soldiers had given us, “Contact C”) and we leveled several compounds with artillery. Somehow we escaped without a scratch, truly amazing.

We were again ordered back to the Sangin District Center with 3 Para and spent the next few days fighting with the Paras. For four days I did not get a chance to take off my Frag vest, helmet or change my socks, etc. We were attacked 2-3 times a day, and always repelled them decisively. I also discovered during this period that exchanging rations with the Brits is a really bad idea. Not only were they stuck in this miserable place but their food was absolutely horrible!

After saying our good byes to our Brit comrades (the enemy learnt their lesson and finally stopped attacking the place), we again prepared to go back home. Alas, it was not to be again. We were ordered South to take back to towns that the Taliban had just taken. Luckily this time after 11 straight days in contact, C Coy. was the Battle Group reserve. We headed to the British Provincial Reconstruction team (PRT). We rolled into the town to the strangest arrival yet. This was coalition country. The locals (unlike Kandahar and even more so in Sangin) were excited and happy to see us. We had kids offering us candy and water instead of begging. There were no Burkhas. The women were in colorful gowns with their faces exposed. The town was booming with shops everywhere and industry flourishing. We went to the PRT and it didn’t even seem real. I took off my helmet, Flak vest and I had a shower and changed my clothes for the first time in two weeks. I ate a huge fresh meal (until my stomach hurt), and then went and sat on the edge of a water fountain in garden and watched a beach volleyball game between the Brits and Estonians. I laughed as I had supper and watched the BBC (British Broadcasting Company) which was reporting that we had taken back the towns, but H Hour was still 2 hours away, so much for the element of surprise. After what we had been through it was hard to believe this place was in the same country. I slept that night (still on the ground beside my LAV because they did not have enough rooms) better than I think I have before in my life. The next couple of days were quiet for us as they did not need to commit us as the reserve. On day 14 of our 3 day op we conducted the 10 hour road move back to KAF, literally limping back as our cars were so beat up (mine was in the best shape in the entire Company and we had a broken differential … again).

Things look like they will be quieter for us now, and I will be home soon. Sad news from the home front, our little Yorkie, Howitzer, was in an accident the other day and didn’t make it. It won’t be the same going home without him, he truly was one of our kids (furkids!). We had three great years with him though and my only regret is that I wasn’t there to comfort Julianne who has been through so much lately. But she has some great friends their who have looked after her. To those of you who have been with her through this and the events of the last few months, I am forever indebted to you.

There are more stories I could tell of these last two weeks but this email has become long enough as it is and if I did that I would have no war stories (I mean state of armed conflict stories) to tell you when I get home. I will end by saying that I have truly enjoyed this experience. Combat is the ultimate test of an officer, and on several occasions I did things that I didn’t know I was capable of. I am so proud of my crew and the entire Company Group, we soldiered hard and long and showed the enemy that messing with Canadians is a really bad idea. We accomplished something in the last two weeks that Canadian soldiers have not done since Korea. The Afghan Government, elected by the Afghans, requested our assistance and we were able to help. We were the equal, if not superior of our allies in everything we did. I hope that I gave you all an appreciation of what these young brave men and women are doing over here, and even if the media can’t find the time or effort to report what we are doing and the difference we are making, hopefully you can pass it on. I will see all of you real soon. I hope all is well with all of you, and please keep the emails coming, I read every one and enjoy hearing from you, even if I cannot respond individually.

Take Care

Andrew

|

Batte For Kandhar |

The Pajawai battle killed the Taliban the rtegime and becama e period of somewhat stability.

| Battle of Panjwaii | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War in Afghanistan (2001–present) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

Governor General of Canadaand Commander-in-Chief of Canada Prime Minister Minister of National Defence | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,000 | 800-1,500 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Canada: 16 killed, 50 wounded U.S.: 2 killed | NATO estimates up to/over 1,000 killed, CENTCOM estimates up to 500 killed throughout whole of period. | ||||||

Solar Streetlights Stabilize Panjawai

New streetlights promote safety, security, and economic development

To provide the people with greater freedom of movement by day and at night, the regional command proposed that USAID install solar streetlights along the road running through Panjawai’s market area. In addition to contributing to safety and security, the streetlights would also support regional stabilization efforts and local economic development.

Panjawai is a major city that lies in the heart of Kandahar Province, a long-time Taliban stronghold. In 2010, Afghan and international military forces conducted clearing operations that drove the Taliban out of the area to protect the people of Panjawai from Taliban interference, intimidation, and violence.

USAID was quick to accept the recommendation and by the end of the year, had erected twelve solar streetlights, which are now providing illumination through the night for Panjawai’s market bazaar and a nearby mosque.Each of the 120 watt streetlights comprises an encased high-efficiency LED lamp, a PV panel, deep-cycle battery, timer, and pole. The PV-powered streetlights are capable of providing light all night long, even after several consecutive cloudy days. They can be used even if electric power is available, as the reduced load and energy savings translate into lower operating costs.The systems are warranted by the installer for two years. The PV modules themselves are guaranteed for 25 years, and future battery replacements are not anticipated until after five to seven years.

USAID and the installer, along with other local renewable energy companies, are planning maintenance and repair strategies, including battery recycling and exchange services.Installation of the streetlights presented USAID and the local installer, Zularistan, with numerous challenges, including customs delays, transportation problems, and security threats. These were ultimately overcome to the satisfaction of Panjawai’s market-goers and In the words of one evening shopper,

“The lights make crossing the road safer, and the shops are open longer. This is a good thing for us!”

|

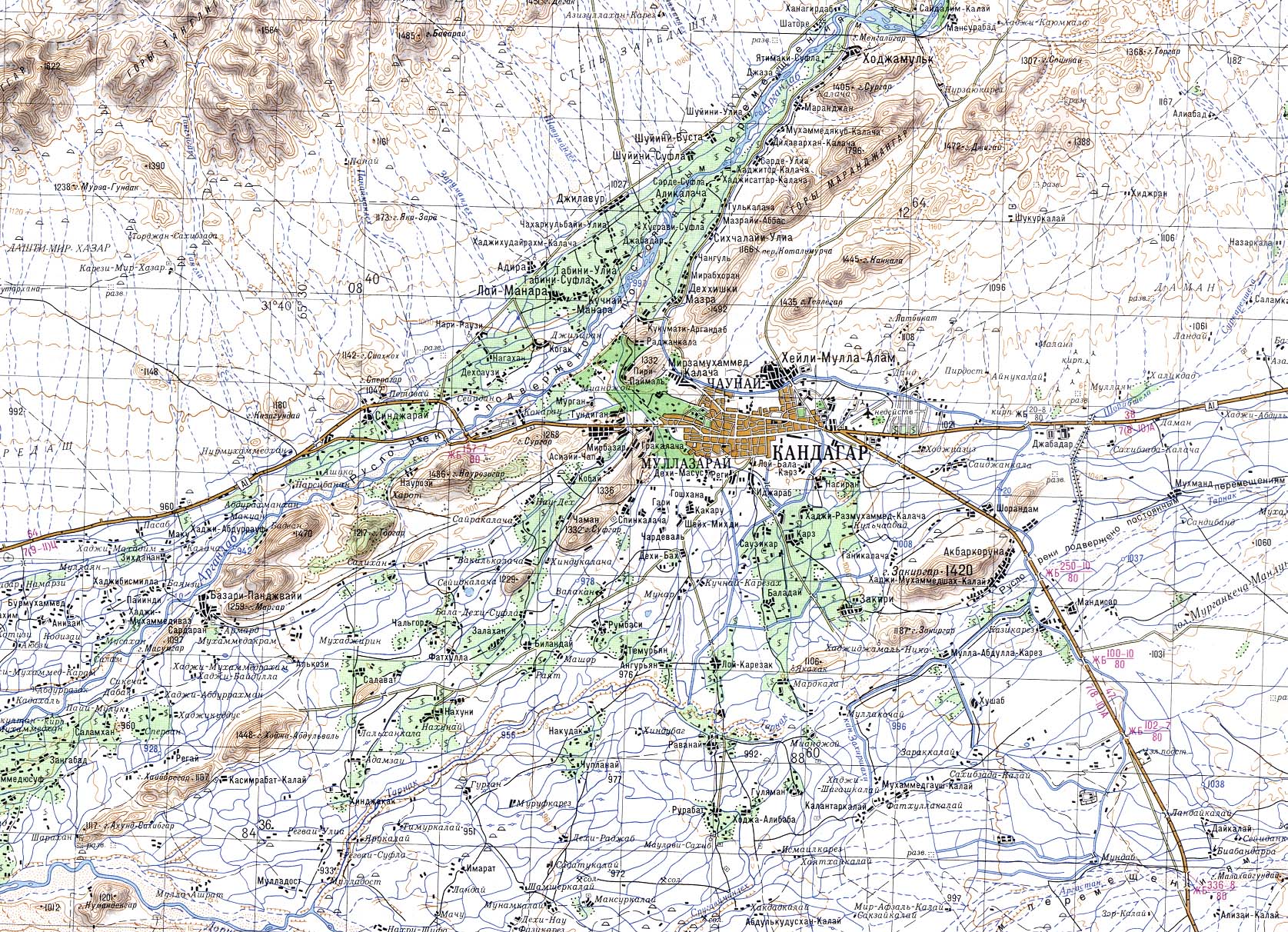

| Old Soviet Russian... Pajwai is to the lower left. |

Part 1: The Long Road

Posted In: Features The Long Road

KANDAHAR, Afghanistan — Corey McCue has seen the worst of the fight for Kandahar, and the best. A 25-year-old combat engineer based in Petawawa, Ont., he is completing his second combat tour in three years. By the time he comes home in July, he will have served almost 600 days in theatre, more than half of them “outside the wire,” living rough and traveling hard. He has experienced two different wars.

Canada’s combat mission in the Afghan province ends formally in ten days. Canadian troops have lately been winning small but important victories, taking far fewer casualties than before, opening new rural roads and schools, and feeling confidant they are making improvements and accomplishing their tasks. But Cpl. McCue remembers another, bloodier conflict. A war that was being lost.

He first laid eyes on this battle-scarred province in September 2008 as a member of Operation Athena, Roto-6. At the time, it was obvious to rank and file soldiers and officers alike that Canada’s military and civilian objectives – to free Kandahar from Taliban violence and threats, to establish capable, local security forces and governance, and to rebuild the province’s crumbling infrastructure -were falling short. From what he could see, “everything was falling apart,” Cpl. McCue recalls.

This was not an isolated opinion. Morale among troops had plummeted. “My men don’t want to come back [for another tour],” one grizzled captain told me several months before Cpl. McCue and his battle group arrived. We were standing inside a remote Canadian-held forward operating base west of Kandahar city. The captain was exceptionally candid. He had already claimed that some of his men were being blamed, unfairly, for handling a detainee improperly. Now he was charging they were all “scared.”

“It’s fucking dangerous out here,” said the captain. Standing beside us was a full colonel. The colonel showed no surprise. He expressed no chagrin. It wasn’t news to him.

Canada’s involvement in Afghanistan was then in its seventh year. The first Canadian troops –elite special forces members — deployed quietly in December 2001, three months after Osama Bin Laden’s al-Qaeda terrorist network had launched its devastating attacks on the United States. The Canadians conducted clandestine operations aimed at capturing or killing al-Qaeda fighters and their Afghan brethren, members of the Taliban. Regular infantry soldiers were sent forward in 2002, and a year later, almost 2,000 troops were deployed to Kabul, to help secure and rebuild the Afghan capital. This was the first rotation of Operation Athena, Phase I. It wasn’t a “traditional” peacekeeping effort, but to many back home, it seemed to fit Canada’s perceived role as a reliable contributor to international relief and security efforts.

The operation’s second and more controversial phase began with a battle group deployment to Kandahar, early in 2006. Canadian soldiers — most of them from 1st Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry — were suddenly in the crucible, responsible for a multinational counterinsurgency campaign in a land of tribal complexities that none claimed to understand, in a physical setting they didn’t recognize, fighting an enemy they struggled to distinguish from peaceful men.

Their war — Canada’s war — had begun.

By the end of 2006, 36 Canadians had died on the battlefield in Kandahar. By the end of 2007, another 29 Canadian soldiers were dead, and an officer in Kabul had committed suicide. Dozens more losses would follow: Lost lives, and lost opportunities. Chaos, mistakes, denials, scrambled facts, anger. Pessimism and confusion, in Kandahar and at home.

Finally, near the end, there were better moments, real accomplishments and even hope. Canada’s efforts in Afghanistan aren’t over, but the most difficult phase has ended. Was it worth the sacrifice, the spent treasure, the pain and the burden put on soldiers and their families? And did Kandahar benefit? To find answers, we return to the scene, to a story that began long before Cpl. McCue first arrived.

Kandahar Airfield, December 2006: Momentum that Canadian troops had seized early in their combat mission was now stalled. Initial battlefield victories, most notably Operation Medusa, a spectacular September 2006 drubbing handed the Taliban by Canadian and other coalition forces in key Kandahar districts of Panjwaii and Zhari, had come undone. While an estimated 500 insurgents were killed during the two-week combat phase of the operation, compared to just five Canadian fatalities, the Taliban quickly reinforced their presence in the two districts. “The Taliban filled back in,” a Canadian officer acknowledged at a December 2006 briefing with reporters embedded at Kandahar Airfield (KAF). The officer put insurgent numbers in two key districts – Zhari and Panjwaii, west of Kandahar city -at 900, greater than Canada’s own troop strength in the two districts.

“Medusa,” he admitted, “did not achieve post-kinetic objectives.” And the Canadians had fallen back on their heels.

There weren’t enough Canadian forces or Afghan National Security Forces [ANSF] on the ground in Kandahar to beat back Taliban fighters, who streamed into the province from training centres in Pakistan. Insurgents came to Kandahar, season after season, and year after year. They considered the province their turf; this was the movement’s birthplace and spiritual home. The International Security Assistance Force, the NATO-led coalition military response to al-Qaeda and the Taliban in Afghanistan, had not mustered an adequate response. Military analyst Carl Forsberg summarized the situation in a report he prepared for the Institute for the Study of War, a U.S.-based non-partisan think tank. “Despite Kandahar’s military and political importance,” he wrote, “ISAF failed to prioritize the province from 2005 to 2009, allowing much of the population to fall under the Taliban’s control or influence.”

Just before Christmas 2006, the Canadians led another large operation in Zhari and Panjwaii. The operation dubbed Baaz Tsuka, or Falcon Summit, was intended to bring material assistance to the local population and disrupt Taliban activities in the two districts. Principal targets were so-called tier-two Taliban, local men of fighting age, most of them poor and illiterate and attracted to the insurgency by the promise of money. ISAF’s plan was to hand them shovels, picks and wheelbarrows, in the hopes they would abandon the insurgency. They would also be offered positions in a new paramilitary outfit, the National Auxiliary Police, described at the time as a kind of armed neighbourhood watch.

The operation went ahead as scheduled and was over by the new year. Logistically, it was a success. Taliban forces had decided not to engage their adversaries; they remained inside walled residential compounds in the two districts as Canadian soldiers unloaded five sea containers filled with hand tools. These were distributed in the two districts. As well, about $50,000 in cash was distributed to local elders, to be used to entice the half-hearted among them to commit to the Afghan government side.

The other objective — to persuade the tier-two Taliban to put down their arms — was not achieved. Few dared abandon the Taliban, let alone leave to join the National Auxiliary Police. The program was soon abandoned. And hard-won territory in Panjwaii fell to insurgents in the new year.

By then, the Taliban’s battle space had changed. Their fighters launched fewer direct attacks and ambushes on well-equipped foreign fighters. Not because they were outmanned; they often had the numeric advantage. Canadian troops were stretched notoriously thin. Each 1,200 member battle group rotation was responsible for securing all of Kandahar, a province similar in size to Nova Scotia. This mean that prior to 2009, the Canadian Forces could spare only two infantry companies – about 180 soldiers – and a small tank squadron to patrol and secure Zhari and Panjwaii districts, where the Taliban had concentrated. Other battle group companies and elements were responsible for protecting districts to the east, to the southeast, and to the northeast, reaching well beyond Kandahar city.

But the Taliban were no match for Canadian guns and tanks, nor the 500-pound precision bombs that American aircraft were prepared to drop on them from the air. By 2007, insurgents relied mostly on quick-and-dirty surprise attacks using small arms, rocket propelled grenades, and home made bombs. In the rural countryside, where most Canadian troops operated, the Taliban found their greatest success planting deadly improvised explosive devices, or IEDs. Using parts sourced from Pakistan and Iran, insurgents buried the bombs under footpaths, roadways, in mud walls and in trees. They were detonated using simple remote controlled devices, or by compression. Toor Jan, a former Taliban commander in Panjwaii, recalled that the “IEDs were fantastic. We would plant them in areas where we knew the foreign troops were coming, and when they came we would just blow them up.”

By the time Cpl. McCue deployed to Kandahar in September 2008, the combat mission had claimed 87 Canadian lives; 42 of the deaths were the result of IED blasts. Nine more Canadians would be dead by the year’s end, all of them victims of IEDs. And in the following year, 32 Canadian soldiers involved in the combat mission would die; all but three were killed by IEDs. (The figures do not include four Canadians killed by U.S. friendly fire during a training exercise near KAF in 2002, and four Canadians killed in other parts of Afghanistan between October 2003 and November 2005, prior to the start of the combat mission in Kandahar).

“I think 2008 was a big step back,” acknowledges Lt.-Col. Michel-Henri St-Louis, commander of Roto-10, the last Canadian battle group to deploy to Kandahar. Lt.-Col. St-Louis arrived in theatre last fall, under very different circumstances, but like every Canadian soldier he was acutely aware of the problems that battle groups had already encountered.

LOSING HOPE

In Kandahar city, insurgents continued to focus on “soft targets” such as Afghan civilians, government workers, elected officials and police. Security remained a distant dream, as did promised improvements to infrastructure. Electricity was sporadic across the entire province. Due to a chronic lack of power, factories sat closed. Unemployment remained high. The public’s frustration boiled. Ordinary Kandaharis – almost a million Muslim men, women and children, most of them illiterate, waging their own battles with disease, poverty, corruption and internecine tribalism – had no love for the Taliban, whom they regarded as tyrannical and cruel, but they remained suspicious of foreign troops and viewed many local government officials with contempt.

About 10,000 internally displaced peoples, or war refugees, were camped north of the fighting zone and in Kandahar city. The refugees were being ignored; international aid money meant to alleviate their conditions and their suffering was being diverted into the pockets of corrupt Afghan officials. The camps had become prime recruiting zones for insurgents.

In 2007, the Canadian Forces hired a polling firm to survey Kandaharis; one question asked was whether they felt “relatively safe” in their communities. A little more than half of respondents answered “yes.” A year later, they were asked the same question; only 25% answered in the affirmative. Brigadier-General Denis Thompson, who commanded Canadian troops in Kandahar in 2008, acknowledged to the National Post that “people’s perception of security has had its legs cut out from underneath it. And that is a result of a change in Taliban tactics. They have gone from being in your face in 2006 and earlier to doubling up the number of improvised explosive attacks and acts of intimidation, such as splashing acid in the face of schoolgirls or executing the deputy chief of police from Kandahar province.”

Violent crime remained a concern. Civilians were being targeted by kidnappers. Sometimes, police were involved in abductions. In July 2008, the Taliban blew open the gates of Sarposa Prison, an archaic penitentiary on the outskirts of Kandahar city, with a massive truck bomb. All 1,000 inmates – including an estimated 400 insurgents – escaped.

The crime wave continued; so did Taliban-led intimidation and murder. Some community leaders began to express frustration with the situation, at the lack of security and at the scarcity of resources and jobs. There were hardships and atrocities under Taliban rule, they agreed, but daily life was even more difficult under the elected national government led by President Hamid Karzai, himself a native of Kandahar. “The Taliban were bad, but they weren’t corrupt,” a Kandahar city university teacher and businessman named Aman Kamran told me in 2008. That wasn’t true; the Taliban had filled their own coffers with profits from the sale of opium, until international pressures forced them to stop poppy production in 2000.

Mr. Kamran made a lasting impression. A native of Kandahar, he had left during the Soviet occupation in the 1980s and worked for years in New York. He became an American citizen. Like thousands of other Kandaharis, Mr. Kamran returned to the province after the Taliban were removed from power. He hoped to build a thriving business and something like a normal life. That didn’t happen. When we met, he had almost lost hope. “Kandaharis have two faces,” he said ominously. “We have been showing our sheep face. Don’t force us or pressure us or we will show our wolf face. Once frustrated enough, the general public will pick up arms. They will wage war on the government and coalition forces responsible for this mess.”

Kandaharis questioned the coalition’s motives and commitments. Why would rich men and women from the West put their lives on the line for some farmers in Panjwaii? And how long would they stay? Canada’s counterinsurgency objectives – winning the battle for local hearts and minds, separating insurgents from the population – were not lost, but they weren’t being won. As for defeating the Taliban, something the Canadian public thought was the goal? That had never been in the cards, admitted Brig.-Gen. Thompson, on his return from Kandahar.

“In a counter-insurgency there is no VE Day and there is no ticker tape parade,” he told the National Post. “There is none of that. It just slowly withers and dies. You don’t defeat an insurgency. You marginalize it. You bring it to the point where it is forced to become just a political movement and then they are just the opposition.”

AT THE HEART OF THE ENEMY

Cpl. McCue paid little attention to the politics of war. Like most enlisted Canadian soldiers deployed for the first time to Kandahar, his understanding of local life and customs was minimal at best. He was posted to Forward Operating Base Sperwan Ghar, as remote a place as he could have imagined. An old Soviet-made mound of dirt and sand, it sits like a giant anthill in the middle of Taliban country, about 30 kilometres west of KAF, on a triangular peninsula called the Horn of Panjwaii. About 160 square kilometres, the Horn is the movement’s traditional seat of power.

FOB Sperwan Ghar was the only significant Canadian position in the Horn when Cpl. McCue landed there in 2008. It was constantly under enemy fire. Helicopters routinely took small arms fire when they flew into Sperwan Ghar. Insurgents could creep into firing position just outside the FOB’s walls. Private contractors hired to chopper supplies to Canadian troops in the Horn would eventually refuse to land at Sperwan Ghar.

FOB Sperwan Ghar was the only significant Canadian position in the Horn when Cpl. McCue landed there in 2008. It was constantly under enemy fire. Helicopters routinely took small arms fire when they flew into Sperwan Ghar. Insurgents could creep into firing position just outside the FOB’s walls. Private contractors hired to chopper supplies to Canadian troops in the Horn would eventually refuse to land at Sperwan Ghar.The dirt road leading into FOB Sperwan Ghar was riddled with IEDs. “My first day in theatre, we dealt with an IED in a culvert, right on the road out front,” Cpl. McCue recalls. “It happened once or twice again after that. The same culvert. There were walls on either side of the road, and the enemy could get right up to the culvert and do their thing, without anyone [in the FOB] noticing them.” The fields surrounding the FOB were also mined.

Despite the dangerous terrain, Cpl. McCue and his mates conducted regular foot patrols; these “dismounted ops,” he recalls, would last one to two weeks. Sections of about ten men walked west from FOB Sperwan Ghar towards a small village called Mushan, near the tip of the Horn where two rivers converge and the Panjwaii district ends. The patrols were meant to demonstrate their presence in the area, and they often led to searches inside suspect dwellings and compounds. Soldiers knew they were also meant to provoke the enemy. “Every time we went west of Sperwan Ghar, we’d get in a fight,” says Cpl. McCue. Always. “We knew that when we went past that [specific position] on a map, we were getting into a fight. It happened every time…We were provoking. The officer in command, he wanted that, but he wouldn’t say ‘let’s go out and pick a fight’.”

Cpl. McCue and his mates could not see the point. “There was definitely an objective for every operation we went on. But, as for the purpose and the outcome, it was almost like there was no hope. We just didn’t know what we were fighting for at the time. It felt like a lost cause. A lot of guys were getting angry, frustrated. We were clearing routes of IEDs, and finding lots. We were winning firefights and coming out with no one injured. Everything we trained for, we did, and we did it really well. But it just seemed we were doing it for no reason.”

Things would get worse. Early in 2009, Cpl. McCue was part of a group posted to a small police substation (PSS) that Canadian engineers had built in remote Mushan. “We went out there to patrol and to build a helicopter landing pad,” he recalls. PSS Mushan was one of four police substations that Canadians had assembled in the Horn over the previous winter. Meant to establish a permanent, visible presence in Taliban-dominated areas and to try and keep open the one road running the Horn’s length, each PSS was manned with Afghan National Police officers and up to eight Canadian mentors, soldiers attached to special groups called Police Operational Mentor and Liaison Teams (POMLT).

Conditions inside PSS Mushan “were pretty shitty,” says Cpl. McCue. “It was falling apart. There was mud everywhere.” The little fort was exposed and offered soldiers minimal protection. Delivering basic supplies – food, water and ammunition – to the four police substations required a massive military effort. Convoys of 70 vehicles or more had to travel dangerous roads or along the Arghandab River bed intersecting the Taliban heartland, on three-day resupply operations. I traveled on one of those journeys in early 2008; despite taking precautions, our convoy hit an IED along the way. On that occasion, no one was killed but a vehicle was destroyed.

PSS Mushan was probably the last place any Canadian soldier wanted to be. In fact, none of the four police substations – built inside villages at Mushan, Talukan, Zangabad and Hajji – were helping secure the Horn of Panjwaii and separate insurgents from the local population. There was a familiar expression in Kandahar: If you don’t stop for a policeman, he will shoot you. If you do stop, he will rob you.

The piecemeal forts were putting people in harm’s way, attracting Taliban fighters like moths to a flame. That was obviously not the intention, says Maj. Eric Landry, an armoured squadron commander from the 1er Bataillon, Royal 22ieme Regiment, based in Val-Cartier, Que. In late 2007 and early 2008, Maj. Landry, then a captain, was the Canadian Forces’ chief military planner in Kandahar, responsible for conceiving operations across the province. “The idea was to put these little pieces of infrastructure along an existing road, that at the time we called Route Foster,” recalls Maj. Landry. “We would maintain that road and put local police along it. We thought that just that presence would increase security. The assumption was that we would patrol around those substations to the point that our zone of influence in the Horn would grow bigger and bigger, and these police substations would connect, and the whole road would be open. But it didn’t work as much as we thought it would.”

The Canadian presence in the Horn was “too risky,” Brig.-Gen. Jonathan Vance acknowledged later. Brig.-Gen. Vance led all Canadian troops in the province, as commander of Task Force Kandahar from February to November, 2009, and again in 2010. “We didn’t have enough resources,” he said. The police substations were of “no use, no value. An island of [coalition troops] that had a 300-metre patrolling radius, and every time we did one of these river-run convoys we risked losses. For what? Nothing.”

All four police substations were dismantled; PSS Mushan was the last to go, in May 2009. The tear-down operations involved hundreds of Canadian and ANSF troops but they were kept quiet; reporters embedded with Canadian troops in Kandahar weren’t initially informed because the withdrawals could only have been perceived as a negative. The Canadians and Afghans who had operated from the substations were posted elsewhere and the territory around them was ceded to insurgents.

While members of the Canadian Forces refused to call the withdrawals from the Horn a defeat, there’s no question they were significant setbacks. “They had to be,” reflected Lt.-Col. St-Louis, commander of the last battle group to deploy to Kandahar. “It fed into the insurgents’ story that the government of Afghanistan, the security forces of Afghanistan, with the coalition, cannot help you, cannot deliver on the promise of security.”

But rural folk living in the Horn of Panjwaii expressed relief they were gone. “We were living in fear when the [Mushan] fort was there,” one local landowner told me in May 2009. “The Taliban would attack it, and of course the Canadians and Afghan [police] would react. Civilians suffered casualties.” With the troops gone, insurgents were “walking round freely and with rifles,” he added. The Horn was lost, for the time being.

THE SURGE

The situation was grim across most of Kandahar province. Institute of the Study of War research analyst Carl Forsberg noted that by mid-2009, “the coalition could rarely hold ground and often avoided the areas of greatest importance to the Taliban…[Taliban] Sanctuaries in Zhari, Panjwaii, and Arghandab supported bomb-making and IED factories, allowed the basing of insurgent fighters and the organization of complex attacks, and were used for shadow courts to which the Taliban would summon Kandahar City residents.”

Within the city itself, Mr. Forsberg continued, “the Taliban conducted dramatic attacks on Afghan government targets and undertook an assassination and intimidation campaign to dissuade the population of Kandahar City from supporting or assisting the Afghan government.”

But help was coming, from the United States. More U.S. troops were on their way to Kandahar Airfield, already the largest military base in Afghanistan and home to some 15,000 soldiers, private contractors, maintenance and service workers from more than a dozen nations. An American troop surge that began in summer 2009 would continue well into the next year. KAF’s population would double.

U.S. Army engineers and contractors on KAF added more housing units, more mess halls, more airfield capacity and a new, $35 million hospital, a state-of-the-art facility made of bricks and mortar that, like the rest of the new infrastructure, seemed meant to last a very long time.

For Canadian soldiers, however, time was running out. Their “military presence” in Kandahar was to have ended in 2009, but Conservative and Liberal members of the House of Commons voted to extend the mission to 2011. This was a remarkable victory for Prime Minister Stephen Harper, since the war was unpopular at home, and the mission’s purpose and objectives were not well understood. Canadian soldiers were dying at a faster rate than soldiers from other nations involved in the conflict, a discouraging fact that the public recognized and even resented. Reports circulated that insurgents captured by Canadian soldiers were routinely abused by Afghan authorities.

The public’s confusion and anger were considered by an independent government panel, chaired by former Liberal Cabinet minister John Manley. It reported to parliament in January 2008 and from that sprang a Special Committee on the Canadian Mission in Afghanistan.

Tasked to examine the conflict and file quarterly, public reports on the mission to conclusion, the parliamentary committee did not mince words. The mission had run into difficulties, it recognized. Moreover, Afghan society was barely advancing. A committee report filed early in 2010 was typically frank. “The Taliban insurgency gained strength and influence throughout 2008 and most of 2009,” it read. “In Afghanistan, profoundly serious issues remain. The death and destruction of the last 30 years has deeply traumatized all parts of Afghan society. Afghan institutions at every level lack capacity, transparency, and accountability.

There is a desperate shortage of teachers, doctors, nurses, and professionals of every kind. Violence and insecurity, among other factors, make it hard to recruit such people in the geographical areas that need them most. The necessary work of reconciliation has proven slow and politically contentious. Corruption is widespread and corrosive. These circumstances exist in the context of a continuing and pervasive insurgency…The objective of ensuring an Afghan state capable of ending internal conflict and providing basic services to its people will clearly not be met before the end of 2011.”

Such conclusions came as no surprise to Canada’s military leaders. Endemic corruption and lack of political capacity and leadership in their own area of responsibility, Kandahar, had impaired their own counter-insurgency efforts and had jeopardized the safety of their own troops. The Canadian public was tired of the stalemate in Kandahar; so were Canada’s most senior military officers, who knew where the real problems lay.

The problems did not rest with their men and women in theatre. From 2006, Canadian soldiers had proven themselves more than capable in their combat role. Their training was excellent and their conduct in battle extraordinary. But the condition and the quantity of their equipment was inconsistent; it ranged from excellent to inadequate. It was no secret that their battle group numbers were insufficient for an area the size of Kandahar.

Looking back at the period from 2006 to 2009, a senior Canadian officer concluded that troops “dealt with the worst military threats posed by the Taliban. We managed. We didn’t lose, but we didn’t win. Some would argue, and I would agree, that we sometimes made things worse.”

But the American surge had a profound and positive impact on the mission. By summer 2010 an additional 30,000 U.S. troops – more than 100 times the number of Canadians in theatre – were deployed in Afghanistan; many of these troops were spread across Kandahar province and in Kandahar city. The surge allowed Canada to concentrate its area of operations to just two districts: Dand, immediately south of the city, and Panjwaii, the perennial battlefield to the west.

CANADA’S LAST BATTLEGROUNDS

The two districts are an interesting study in contrasts. Now synonymous with the Taliban, Panjwaii is fertile and agricultural; most of its 30,000 inhabitants depend on farming for their livelihoods. The landscape is divided by walls demarcating villages, family compounds and fields, and by myriad irrigation ditches and dirt tracks. The tight grid-work pattern make perfect terrain for guerrilla warfare, especially in the verdant summer, as it offers plenty of ground cover to insurgents on foot and creates one obstacle after another to conventional land forces mounted in armoured vehicles.

Dand, on the other hand, is arid, open, and sparsely populated. Although the Taliban have launched attacks on troops there, it is not a major insurgent base and has presented fewer challenges to Canadian soldiers. Dand’s district governor – a position equivalent to the chairman of a regional municipality in Canada – is Hamdullah Nazik, an affable, educated man in his thirties whom coalition soldiers and senior diplomats trust. Compared to Panjwaii, Dand is an oasis of calm.

But by March 2009, “the district was about to fall,” recalls Brig.-Gen.Vance, who commanded troops in Kandahar that year. The Taliban had managed to attack Dand’s district centre, a walled government compound where Mr. Nazik worked and where limited public services were offered to locals. Most of the infrastructure was destroyed. The successful insurgent strike on the district centre signalled again that Canadian troops and their Afghan partners did not provide blanket protection.

To restore local confidence, Brig.-Gen. Vance redoubled Canadian efforts in the district. He conceived of an ambitious reconstruction and rehabilitation campaign that would initially see the shattered district centre restored and improved, with more government services offered there, and physical improvements made to a village called Deh-e-Bagh. The district centre and Deh-e-Bagh would be presented as models of progress, positive examples of what might be accomplished should Afghan elders in other settlements put their faith in coalition troops and work with them, rather than submit to Taliban threats.

Brig.-Gen. Vance hoped to expand this “model village” approach program across the district and then into Panjwaii. He enlisted the help of an American military professor and counterinsurgency expert named Thomas Johnson. This was an interesting choice; Prof. Johnson was already a fierce critic of the U.S. military’s approach to counterinsurgency in Afghanistan. He notoriously compared the war against the Taliban to another counterinsurgency, one waged a generation earlier in Vietnam, and he dismissed a large British and American-led operation in the province of Helmand as “essentially a giant public affairs exercise, designed to shore up dwindling domestic support for the war by creating an illusion of progress.” He was no fan of the country’s president, Hamid Karzai. Prof. Johnson would characterize President Karzai’s August 2009 re-election as “rigged” and “a disgrace.”

To independent observers of the war in Afghanistan, this was a refreshingly honest and informed perspective. It was also completely at odds with the official ISAF view; one never heard, for example, a Canadian general in Kandahar disparage either the coalition’s efforts or the Afghan president, at least not in public.

But Brig.-Gen. Vance was obviously impressed with Prof. Johnson. He invited him to Task Force Kandahar headquarters at KAF, and together they designed the new Dand district strategy.

Roads were paved and solar-powered street lamps were installed in Deh-e-Bagh. The district centre was refurbished and a courthouse was built. Security rings went up around other district villages and population clusters, and infrastructure was rebuilt to improve economic development and governance.

But the Taliban did not throw down their arms and concede. In September 2009, insurgents attacked a Canadian convoy as it traveled near Dand’s district centre. One soldier was injured when his light armoured vehicle (LAV) was stuck. As it happened, Brig.-Gen. Vance was close by in another vehicle. He immediately called a meeting, or shura, with local elders. According to Canadian Press reporter Bill Graveland, who was also on hand, the general was furious.

“It disgusts me that my soldiers can be hurt,” Brig.-Gen. Vance told the elders. “If we keep blowing up on the roads I’m going to stop doing development. If we stop doing development in Dand, I believe Afghanistan and Kandahar is a project that cannot be saved.” Brig.-Gen. Vance said he expected the local population to cooperate with coalition and Afghan soldiers, and to report suspicious activities. Elders nodded their heads as if in agreement, but as always, it was impossible to know where their confidence lay.

Insurgent attacks continued in Dand. In late December 2009, four Canadian soldiers – Sergeant George Miok, Sergeant Kirk Taylor, Corporal Zachery McCormack, Private Garrett Chidley – and Calgary Herald reporter Michelle Lang were killed when the LAV in which they were traveling was hit by an IED. A reporter in Toronto tracked down Prof. Johnson and asked him to comment on the deadly incident. “I’m shocked that the bombing would have happened in Dand,” he said. Then he raised the obvious: Insurgents, he said, “might have had an explicit objective to discredit the Canadian model village project.”

Attempts were made on the district governor’s life; all of them failed but a dozen village leaders in Dand were reportedly assassinated. Yet security in the district had noticeably improved by summer 2010. Some Afghan acquaintances of mine, local men who had refused to travel into Dand the previous year, suddenly determined it was safe. For his part, Brig.-Gen. Vance was determined to show that his counterinsurgency formula was working. “They’re actually dealing with the finer points of political assembly in Dand right now,” he insisted, during an August 2010 interview with reporters embedded with his troops.

A few weeks later, he invited three of us on an excursion into the district centre. After a meeting there with American soldiers under his command, Brig.-Gen. Vance announced he was venturing outside the walled compound for a stroll. He removed his body armour; until then, I had never seen a Canadian soldier – let alone the most senior officer in Kandahar – do such a thing in the open. We followed suit. We walked outside to a freshly paved intersection, and we stood there, completely exposed. A crowd of villagers formed around us. Some local children challenged a pair of soldiers to a foot race. Off they all ran, arms flailing, hats flying, the children screeching with delight.

I’d first come to Kandahar in 2006; this was the first time that I had sensed any real hope.

Bigger changes were to come. In September last year, U.S. and Afghan forces launched major campaigns in Zhari and Panjwaii districts. These represented the final phase of a three-stage operation designed to secure the most populous parts of Kandahar province and to push the insurgency there to the brink. Dubbed Hamkari, the Pashto word for “cooperation,” the operation launched in June with the establishment of Afghan police road checkpoints around Kandahar city. These were intended to prevent insurgents from entering the city; in practice, they didn’t work. Then came an American-led clearing operation in Arghandab district north of the city. This battle was hard fought and longer than anticipated; the Taliban mounted a stiff challenge but were ultimately handed a defeat. U.S. and Afghan troops held the territory they had cleared, and attempted to win over local families who had suffered their own losses during the fighting.

A similar scenario unfolded in Zhari, where U.S. and Afghan troops fought the Taliban from mid-September to October. Some of the district was cleared, but not all; parts of Zhari remains under Taliban control. Phase Three in Panjwaii then kicked off, with U.S. special forces, U.S. infantry, and Afghan National Army elements entering the Horn and taking the key villages of Zangabad and Mushan. The village of Talukan, in the middle of the Horn, was claimed last. Meanwhile, Canadian troops protected their hard-won positions in eastern Panjwaii, in villages such as Nakhonay, Salavat and Chalghowr.

Demoralized by their defeat in the Arghandab, battered in Zhari, and with much of their local leadership killed off by U.S. special forces, the Taliban barely mustered a fight in the Horn. Their sanctuary was taken with relative ease. But more work was required there, and more troops. The Canadians knew the terrain. They were going back, this time with renewed purpose.

THE LONG ROAD

Former operations planner Eric Landry returned to Kandahar in late November, this time in command of a 60-person tank squadron, an element of 1er Bataillon, Royal 22ieme Regiment. Maj. Landry’s legendary “Vandoos” had the honour and burden of leading Canada’s last battle group in Kandahar. They were motivated by opportunity: Finish the long and contentious combat mission on a high note.

Conditions looked their best since 2006. Maj. Landry figured he’d barely be tested. “I thought I was going to come and sit here and once or twice a month do a little operation, attach a group of tanks to the infantry, and not really be in charge of anything,” he recalled later. That’s not how things went.

The Taliban had melted away, but they hadn’t left. Supply routes in the Horn remained exposed and under IED threat. American soldiers still holed up in Zangabad, Talukan and Mushan “had no road access, no ground lines of communication, and had to be resupplied by air,” says Maj. Landry’s battle group commander, Lt.-Col. Michel-Henri St-Louis. “They were maintaining their presence in the Horn from a pretty tenuous position. They were waiting for us to arrive.”

ISAF headquarters in Kandahar worked on a solution. On November 28, Lt.-Col. St-Louis was handed his mandate: Build a wide road, from a point north of FOB Sperwan Ghar and running westward, through Mushan and beyond, into the very tip of the Horn, where the Taliban still moved freely. Build across farmers’ fields. Knock down their grape and poppy field walls, and, if you must, knock down their houses. Arrange for their compensation. Pave the road, all 14 kilometres. Create connecting routes to coalition and ANSF positions at Zangabad and Talukan. Get started now, and have it all finished before the summer fighting season.

Lt.-Col. St-Louis delegated this “daunting task” to his young tank squadron leader, Maj. Landry. “It was a big deal for us,” the major recalled. “We were going to push into the Horn. It was the biggest challenge of our lives. So I was ecstatic. And I was nervous. I knew it was going to be complicated, and I wasn’t trained to do it.”

Maj. Landry had never overseen construction of a road before, but he had helped plan an earlier road project in Panjwaii. It was meant to tie the largest village in the district, Baazar-e-Panjwaii, to FOB Sperwan Ghar, a few kilometres to the west. An offshoot of Operation Baaz Tsuka, the project was started in early 2008 and abandoned that summer. “The assumption was that we would employ 400 local people and take away their temptation to join the insurgency, by handing them picks and shovels,” Maj. Landry recalls. “The idea was good but it went way too slow. We paved 1.5 kilometres in four months. We dedicated too many resources to it. I think it was just too time consuming.”

The new road would have to be better and safer. Maj. Landry and his team members went straight to work. He had to get the local population onside. “We first had a big meeting at the [Panjwaii] district centre, where the people gave me all their ideas for the road and what it should look like,” recalled Maj. Landry. The farmers wanted the road to follow Route Foster, which bends and twists and runs through or close to their main villages. But this wasn’t at all what ISAF had in mind. Compromises had to be reached, and negotiations took time.

Meanwhile, American troops were leaving Zangabad and replacements were needed there. Lt.-Col. St-Louis deployed 150 of his Vandoos – A-Company – to the village, where conditions were typically austere. The Americans had been encamped in an old school compound, which the Taliban had used as a command centre and as the seat of their shadow government and court. “That’s where we set up,” says Lt.-Col. St-Louis. “For the longest portion of our tour, we occupied the insurgent’s symbol of power in the Horn. The guys were bedding down in the courtyard of the school where five months prior, Afghan villagers who co-operated with ISAF were hanged. And they would be left there, as deterrents for other Afghans not to co-operate with the ANSF and the coalition.”

Captain Gabriel Benoit-Martin and a 40-member platoon he commanded were the first Canadians to arrive. “It was in a sad state,” he says. “The Americans had left and we found a few [fresh] booby traps, some IEDs.” But the local “pattern of life” in and around Zangabad, was, “surprisingly good,” Capt. Benoit-Martin recalls. “We thought it would be hell on Earth, but the locals were very happy to see us.”

The roadwork commenced in December. Maj. Landry’s team was supplemented by Americans, a crew of Puerto Rican combat engineers, plus Afghan contractors hired to do the road paving. They built 200 metres of road at a time. Armoured vehicles first cleared a path, and the route was shaped, graded, and gravelled. The paving came last.

The new road — called Route Hyena — was nearing completion when I visited the site two months ago. The men had endured freezing winter temperatures, spring flooding, blazing heat. Spiders and snakes. But these were minor hardships.

Everyone on the road was exposed to insurgent attack and to IED strike. The Vandoos suffered an early casualty. On December 18, Corporal Steve Martin was conducting a clearance operation next to the road, at a point between Zangabad and Talukan. He walked around a walled compound. There was an explosion. Cpl. Martin was killed by an IED. He was 24.

In March, the village leader — or malik — was killed in a suicide attack launched from the bazaar. Two civilian truck drivers were also killed. Two Canadian soldiers and five Americans were wounded.

When I visited, Afghan civilians paced warily on the roadside. Some were armed with machine guns and grenade launchers. They were private civilian contractors, hired to protect the Afghan road paving crews. Gravel trucks lined the route; many of their windshields were shot through with bullet holes.

“We’ve found minefields everywhere,” Capt. Adam Siokalo, the tank squadron’s second-in-command, told me, as we stood on a segment of freshly paved road, metres from where Cpl. Martin had died. “We still have [enemy] contact almost every day. Most of it is harassment fire from grape fields, places without road access. It’s hard to get at them when they are shooting at us from the fields. But we’ve also found lots of their caches, weapons, mortars, guns, and ammunition.”

We continued heading west, towards the end of the road. Into Mushan, which I had last visited in 2008. We were to stop there, but Capt. Siokalo received a report warning of a possible suicide attack. We pushed ahead another kilometre, and met up with a small Canadian reconnaissance squadron. A small group of soldiers were camped at the side of the new road, watching for enemy activity. This was a lonely, exposed spot. We didn’t linger.

We moved instead to the end of Route Hyena, where all progress stopped. On one side sat an empty white schoolhouse, its walls etched with drawings: Helicopters, scenes of war. Next to the empty school was a guard tower, manned by a handful of Afghan National Civilian Order Police, an elite unit of officers. They looked west, towards the narrow tip of the Horn and the furthest reaches of Panjwaii district. In that direction, they said, are more Taliban. Beside the guard tower sat a 60-tonne Canadian Leopard 2A6M tank from Maj. Landry’s armoured squadron. As long as it remained there, its cannon pointing west, we were safe.

I thought of the men and women who have died along this route, behind it, and beyond it. I thought of the soldiers who have survived their tours, and of those who have returned to Kandahar, once, twice, three times. Returning soldiers such as Corey McCue, who has seen the very worst of the mission, and, at the end, its best. “I’m not saying I’m really tough or anything, but what guys were doing in ’08 compared to what guys are doing now, this is a breeze,” Cpl. McCue told me back at KAF. “And going all the way down to the Horn like that? That road is pretty much saying to the Taliban, ‘In your face.’”

But he’s leaving. The Canadians are leaving. American troops and equipment are now filling in the space, but they won’t stay forever. When will Afghans be able to protect themselves and defend their fragile, teetering country? The end of the road is just 40 kilometres from Kandahar city, the Taliban’s holy grail.

bhutchinson@nationalpost.com

All illustrations by Richard Johnson, National Post.

Contact the illustrator: rjohnson@nationalpost.com

www.newsillustrator.com

Contact the illustrator: rjohnson@nationalpost.com

www.newsillustrator.com

Part 2: Our legacy in Kandahar

Posted In: Features

For better or worse, Canada’s legacy in Kandahar is left in the hands of men such as Mussa Kalim. He’s the 22-year-old malik -Pashto for appointed leader -of Salavat, a village of about 1,500 battered souls in Panjwaii district, west of Kandahar city.

Like others in the area, his village is poor and primitive, a place where raw sewage trickles down streets, where children run barefoot. In rural Panjwaii, women are kept with livestock behind walls of mud and straw.

Salavat might seem too small or insignificant -and Mr. Kalim, pictured below, too young -to have warranted more than passing notice from Canadian soldiers on their deployment to Kandahar in 2006.

And yet this village and others around it became a preoccupation, first as battle scenes and, more recently, as centres of reconstruction. They would epitomize Canada’s campaign in Kandahar province.

The Canadian mission, which ends formally in Kandahar on Tuesday, was never limited to combat; it always included elements of development and nation-building. Mending the province’s villages and its shambolic capital, Kandahar city, and trying to nurture governance and rules of law required more than military resources and diplomacy, more than machinery, bricks and talk. Experts from cities across Canada arrived in droves. Civil servants, relief workers, private-sector employees. Doctors, lawyers, engineers, police officers.

Their efforts were ambitious, technical and expensive. They ranged from training teachers and building dozens of schools in conflict zones to mending broken infrastructure, such as Kandahar’s massive, neglected irrigation system, integral to the province’s agrarian economy. They included attempts to pull from the Middle Ages its policing and judiciary, and rehabilitating its largest prison, the notoriously assailable Sarposa.

Hundreds of millions of dollars were spent and some were no doubt squandered.

Progress was slow, and delayed by fear, interrupted by bursts of violence. The Taliban were not defeated; they never left. They continued to threaten and to kill Afghans who dared assist Canadians in their endeavours. Meanwhile, some civilians looked for opportunities to help only themselves.

At times, Canada’s sacrifices were crassly exploited. Reconstruction projects and attempts to fashion some kind of peace depended on sincerity and commitment, two components in short supply. Local partnerships and alliances were inscrutable. To many Afghans, everything seemed negotiable, including trust.

From this complex environment emerged Mr. Kalim. He became an unlikely leader and Canadian ally. He’s not a powerful and charismatic figure like Panjwaii’s barrel-chested district leader, a former mujahedeen warrior named Hajji Fazluddin Agha. Nor is he feared, like the local drug lords and some land owners.

With little, if any, property to his name and only four years of primary school education, Mr. Kalim has more in common with the marginalized, illiterate tenant farmers who eke out their meagre livings in and around Salavat. But he has some influence, or so the Canadians hoped.

His father was the malik until he was murdered three years ago. He had taken a trip into Kandahar city to speak with government officials. A dozen Talibs stopped his car on his return journey. They demanded to know every passenger’s name. They had found whom they were looking for. They dragged the malik from the vehicle and shot him in the head.

Young Mr. Kalim and the rest of his family moved to safer ground in the city. The Taliban, meanwhile, ran roughshod over Salavat. Indeed, some villagers welcomed them back; the local mullah is said to be friendly with Mullah Omar, the one-eyed cleric who was head of state, Commander of the Faithful of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, until his Taliban government fell in late 2001. He fled Kandahar and is believed to be living in Pakistan.

According to an AfghanCanadian hired to help Task Force Kandahar understand local affairs, Salavat “has close ties to the Taliban. It’s a very conservative town. It’s name means ‘prayer.’ ”

The village and its surroundings crawled with insurgents. Roads and fields were seeded with improvised explosive devices (IEDs). But Canadian soldiers settled near Salavat in 2009 and used an old school and its small compound as an outpost before building a larger and more fortified forward operating base next door.

Holding Salavat was difficult and no reconstruction efforts were possible. But last year brought noticeable improvements in security, especially after the third and final phase of Operation Hamkari, a major coalition clear-and-hold operation in Panjwaii and Zhari district to the north. U.S. and Afghan troops claimed territory that had been controlled by the Taliban in the western half of Panjwaii, and Canadian troops consolidated and expanded their influence in the other half, in and around villages such as Salavat, Chalghowr and Nakhonay.

By December 2010, Canadian soldiers were rebuilding the damaged Salavat school compound, with some help from locals. Work continued in the new year; the small concrete classrooms were painted, inside and out, and basic playground equipment and solarpowered lights were installed in the yard. Finishing touches were completed by March. The Canadians had done their part, as they had many times before.

And Mr. Kalim took a bold step. He formally pledged his support for the Canadian effort and to the Afghan government.

With approval from Mr. Agha, the new Panjwaii district governor, pictured below, Mr. Kalim replaced his father’s successor and became malik. It was now up to him to represent Salavat at local government level and ensure its residents were participating in small development projects undertaken there, including clearing irrigation canals.

Villagers were paid for their work; Canadian civil-military co-operation (CIMIC) soldiers stationed at the forward operating base supplied the cash, and Mr. Kalim was responsible for handing it to the people.

He was also asked to help convince parents that sending their children to the refurbished school would be a blessing. Of course, the Taliban had a different message. Send your children to school, they threatened, and face the consequences: injury or death.

The school sat empty. Salavat was at a tipping point.

Mr. Kalim was a visible presence in the village, but only during daylight. In the evenings, he returned to his family in Kandahar city. He felt they were safer there.

They probably were. Kandahar’s capital is a sprawling urban centre, with a population of about 750,000. It’s easier to live there without being noticed than in a small, rural village. Those with means can build a fortress and hire armed guards to protect it.

But it’s still one of the world’s most lawless, dangerous cities. Suicide bombings and IED attacks erupt almost daily. The Taliban target, ambush and kill government workers in the streets, inside government buildings, even inside mosques. More than 50 provincial and municipal government workers, politicians and security officers have been assassinated in the city in the past three years alone. Ordinary Kandaharis face enormous risks, too, just leaving their homes and trying to go about their ordinary business.

Insurgents run amok, and so do common criminals. Kidnappings are all too common. Three years ago, with security in the city not yet at its worst, I met a nine-year-old boy named Abdul Walid Zalal. He was grabbed from a downtown street as he walked home from school, and shoved into a car.

He described how his abductors drove him to a location far from the city, and stuffed him into a cage in a basement. There were other boys there, in cages, Abdul recalled. He also recalled peeking out from the underground bunker and glimpsing Afghan National Police (ANP) vehicles parked in the kidnappers’ compound.

The abductors contacted his father, a local glassware wholesaler. He was told to fork over US$200,000 or Abdul would be cut into pieces and shot.

“I approached the police when my boy was taken,” the father told me. “And the chief himself told me to pay off the kidnappers. A couple of times I was even sitting with the police chief when the kidnappers called to tell me they were going to cut off the boy’s leg or ears. The police chief just sat there.”

A smaller ransom was paid and Abdul was released.

A few weeks later, in February 2008, three ANP officers went on trial, accused of kidnapping and repeatedly sodomizing another local man and his 12-year-old son.

Their case was heard by a local judge and proceeded at lightning speed; the entire process, including testimonies, deliberations and sentencing, was conducted in an hour. None of perpetrators was represented by counsel.

It was a month of horrible violence. Hundreds of Kandaharis gathered just outside the city for some rare entertainment. Dog fights are considered a legitimate sport in Kandahar. Five Afghan National Auxiliary Police officers were in attendance, along with their commander, Abdul Hakim Jan. In fact, Mr. Jan had entered a dog in the competition.